Aldo Leopold is considered an icon of the environmental movement―primarily for his call for a heightened environmental consciousness in the form of a “land ethic.” Leopold writes, if people would learn to “think like a mountain,” they would better understand the complexity of environmental systems and could better conserve them. Developing such a consciousness is obviously difficult; hence many environmentalists call for interim command-and-control policies to force the heightened consciousness. Overtime, Leopold’s land ethic inadvertently became an integral part of the foundation for today’s environmental regulations.

Yet, Leopold was one of the first to raise concerns over the problems inherent in centralized natural resource management. In “The Round River” Leopold uses a story about his bird dog named Gus to point out problems with the progressive conservation of the time. When Gus couldn’t find pheasants he became excited about meadowlarks. This “whipped-up zeal for unsatisfactory substitutes masked the dog’s failure to find the real thing,” which temporarily calmed the dog’s inner frustration. He goes on to explain that he did not know which dog in the field caught the first scent of the meadowlark, but he did know that “every dog performed an enthusiastic backing-point.”

The meadowlark symbolized “the idea that if the private landowner won’t practice conservation, let’s build a bureau to do it for him.” Like the meadowlark, this substitute has some positive points and often smells like success. The problem is, however, “it contains no device for preventing good private land from becoming poor public land. There is trouble in the assuagement of honest frustration; it helps us forget we have not yet found a pheasant.” He concludes by cautioning the reader to be leery of the belief that government will fix “whatever ails the land.”

During the depth of the Great Depression, Leopold increasingly emphasized the importance of personal stewardship of the private landowner. In a major address, “Conservation Economics” found in The Essential Aldo Leopold, he formulated his ideas on private stewardship by critiquing the effectiveness of conservation through public ownership and governmental agencies. He described conservation “experts” working at cross purposes and suggested that economic incentives might reward good stewardship by private individuals.

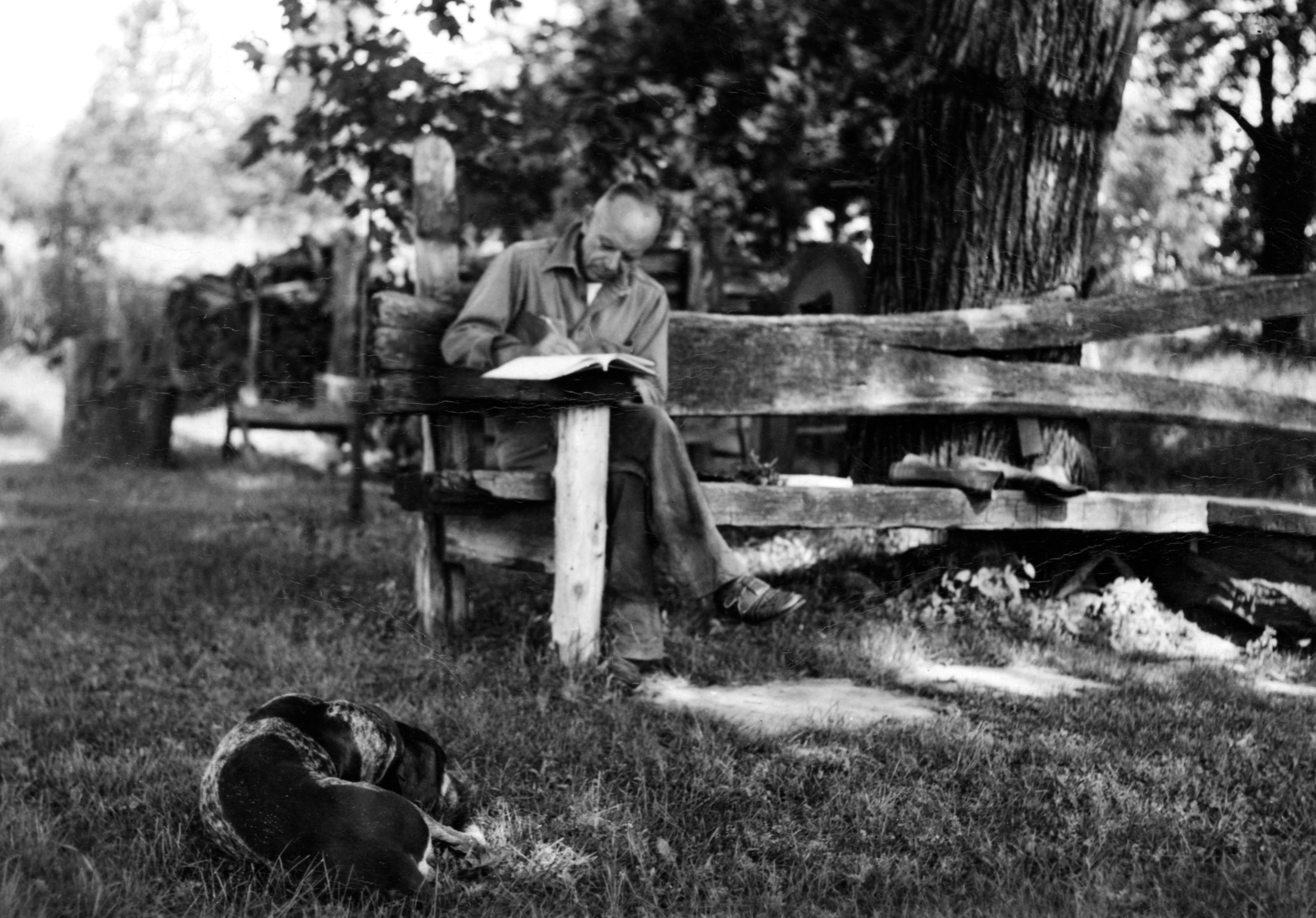

Toward the end of his career, ownership norms and economic incentives played a decreasing role in his writings as he spent more time focusing on ethical obligations. Yet, even as he submitted his land ethic to the public, he wore the hat of the private property owner planting trees around his “shack” in Wisconsin.

Leopold was ahead of his time in coming to the realization that incentives are more effective when they come in the form of the market carrot rather than the regulatory stick. Writing at a time when New Deal policies were at their zenith, Leopold was skeptical that federal conservation programs would achieve their stated aims. As he might have predicted, agricultural subsides led to more intensive farming using more water, fertilizer, and pesticides—all with adverse environmental consequences. Subsidies were hardly the kind of “rewards” that Leopold had in mind.

Aldo Leopold is admired by environmentalists for his “thinking like a mountain,” and by environmental entrepreneurs for his “conservation economics.” Putting these two together allows us to move beyond environmental regulation to achieve practical solutions through free market environmentalism. As he wrote so eloquently in “Land Pathology,”

“Conservation means harmony between man and land. When land does well for its owner; and the owner does well by his land; when both end up better by reason of partnership, we have conservation. When one or the other grows poorer, we do not.”

For more on Aldo Leopold and the roots of conservative environmentalism check out “It’s Aldo, Not Teddy” in Greener Than Thou by Terry Anderson and Laura E. Huggins!