Linking to a new study at Oregon State which tends to reinforce the ecological importance of wolves to the Yellowstone ecosystem and elsewhere. With the wolves helping to reduce the large population of elk in the park, who over the years overgrazed plants, trees and shrubs, many of the berry producing shrubs have returned. These berries are important for the grizzly bear’s pre-hibernation diet.

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new study suggests that the return of wolves to Yellowstone National Park is beginning to bring back a key part of the diet of grizzly bears that has been missing for much of the past century – berries that help bears put on fat before going into hibernation.

It’s one of the first reports to identify the interactions between these large, important predators, based on complex ecological processes. It was published today by scientists from Oregon State University and Washington State University in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

The researchers found that the level of berries consumed by Yellowstone grizzlies is significantly higher now that shrubs are starting to recover following the re-introduction of wolves, which have reduced over-browsing by elk herds. The berry bushes also produce flowers of value to pollinators like butterflies, insects and hummingbirds; food for other small and large mammals; and special benefits to birds.

The report said that berries may be sufficiently important to grizzly bear diet and health that they could be considered in legal disputes – as is white pine nut availability now – about whether or not to change the “threatened” status of grizzly bears under the Endangered Species Act.

“Wild fruit is typically an important part of grizzly bear diet, especially in late summer when they are trying to gain weight as rapidly as possible before winter hibernation,” said William Ripple, a professor in the OSU Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, and lead author on the article. “Berries are one part of a diverse food source that aids bear survival and reproduction, and at certain times of the year can be more than half their diet in many places in North America.”

When wolves were removed from Yellowstone early in the 1900s, increased browsing by elk herds caused the demise of young aspen and willow trees – a favorite food – along with many berry-producing shrubs and tall, herbaceous plants. The recovery of those trees and other food sources since the re-introduction of wolves in the 1990s has had a profound impact on the Yellowstone ecosystem, researchers say, even though it’s still in the very early stages.

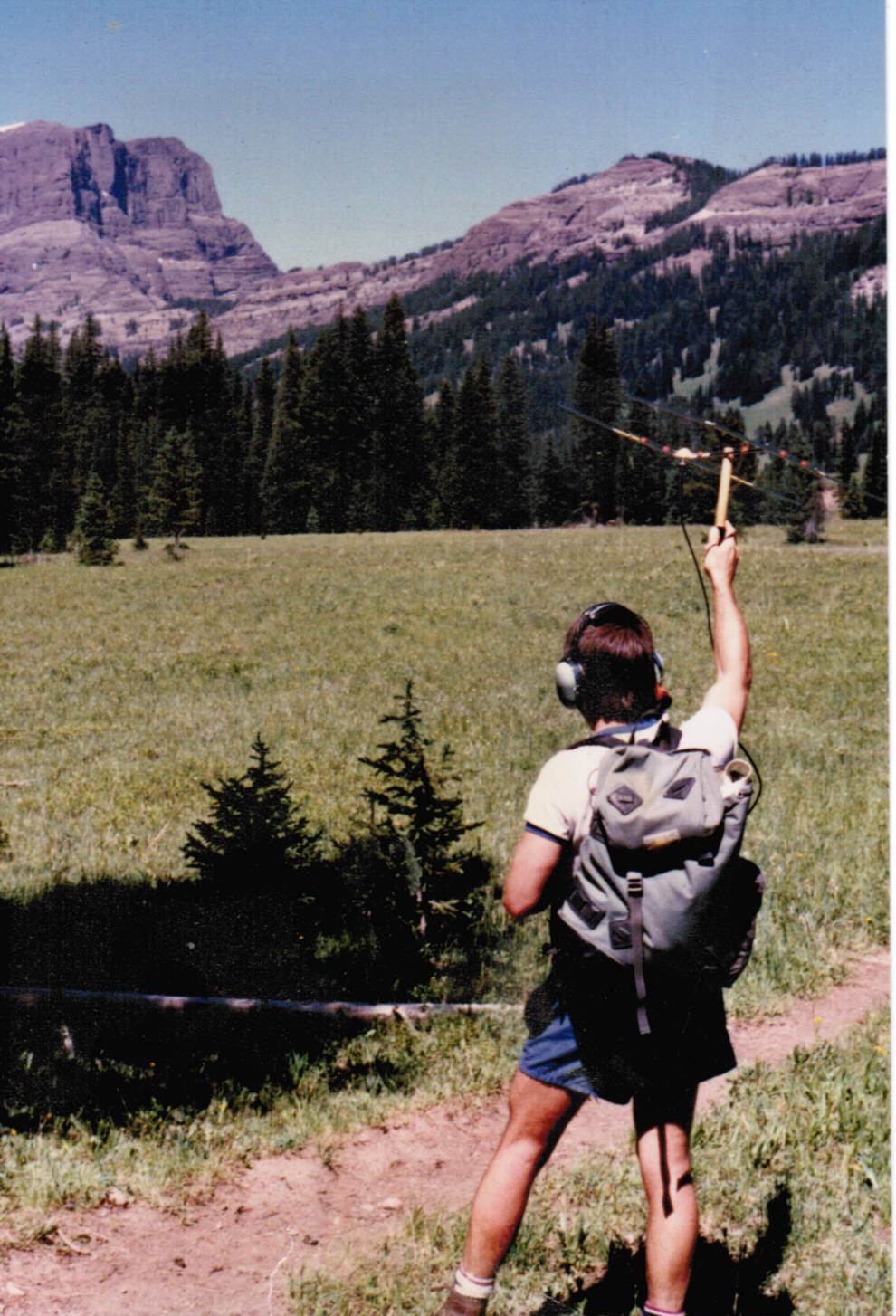

I’m not at all surprised by these results. When I worked in Y’stone in 1988, the physical signs of an ecosystem out of balance were apparent everywhere one looked. You can see from this picture from the upper elevations of Lamar Valley area (that’s Bert Harting, my former boss with our radio telemetry equipment out tracking elk), even off the beaten path, the fields had been so overgrazed, it looked as though they had been mowed by a commercial lawn service.