The water sector seems to be completely immobilized by the canard that a stormwater management fee tied to impermeable surfaces-parking lots, roofs, sidewalks, streets-is a species of “rain tax.” The phrase is waved about like a bulb of garlic before a vampire. This is an abuse of the English language and a distortion of a perfectly reasonable, incentive- or market-based approach to financing solutions to one of the biggest urban water quality challenges in the 21st century. On the Chesapeake Bay, agriculture is the biggest source of pollution, but stormwater is the fastest growing.

An impermeability fee is also a great way to encourage or “incentivize” low-cost green infrastructure techniques that also provide multiple benefits such as mitigation of urban heat islands, energy efficiency and urban beautification.

There is no such thing as a “rain tax.” See below.

This is not to argue that a pavement or impermeability fee is always the necessary or only way to finance a city’s stormwater program. That is a quintessentially political question to be determined by a community’s democratic process. A town can certainly opt for dipping into general revenues, property taxes or some other version of a stormwater fee to get the job done. I am told that Montgomery County, MD funds a suite of stormwater programs, including outreach for green infrastructure on private property, through a Water Quality Protection Charge, part of its property taxes. There are always several ways to skin a cat.

But the hygiene of the political process demands that we be precise, not to mention honest, with the language used to describe policy questions. The right words are necessary to express ideas. And, as Richard Weaver famously said, ideas have consequences. Allowing the “rain tax” charge to go unchallenged is to permit the debasement of the political conversation.

I first saw the “rain tax” label deployed in a drive to rollback a permeability fee in Lansing, MI while I worked on Great Lakes issues in the 1990s. It worked amazingly well. The fee was rescinded. Countless headlines and broadcast news stories repeated the mantra that this was some kind of silly tax on rain falling from the heavens above.

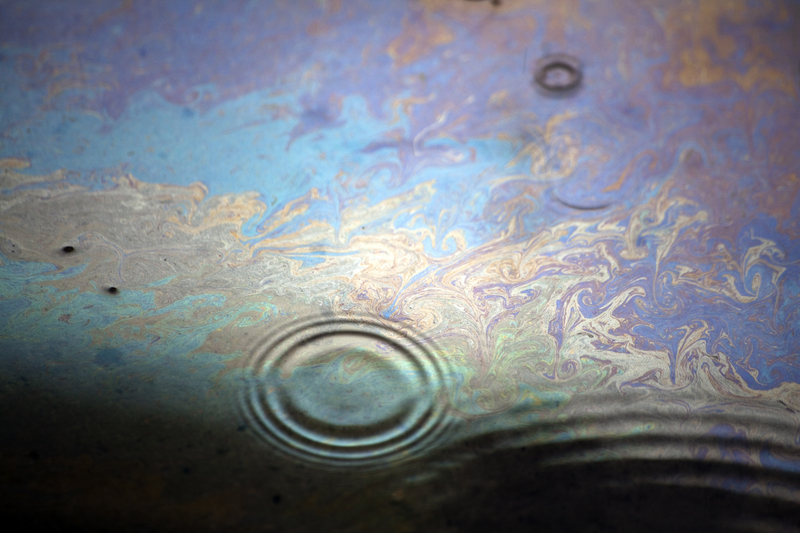

This is simply not the case. If it were, the fee would have been calculated based on the volume of precipitation. A fee on impermeability, concrete, pavement or other hard surfaces is related to the amount of surface over which stormwater flows carrying with it numerous pollutants while raising water temperature and driving higher velocities. This, in turn, blows out the biota in streams, destroys vegetation and accelerates erosion. This latter phenomenon results, eventually, in putting the stream in a concrete box that only aggravates the process. So the permeability fee has a close nexus to the cost of managing stormwater runoff from a given surface area. Very logical.

Surely, some clever consultant or public relations guru can formulate a rival concept or moniker to deconstruct the misleading “rain tax” label and give voters and political leaders a clearer idea of the issue and the reasons to consider a stormwater fee on impermeability. Part of the story should describe how fee reductions or offsets for green practices such as green roofs, rain barrels, vegetated swales, urban tree planting and gardens designed to capture runoff could reduce the fees over time. The goal, of course, is to allow more stormwater to be infiltrated, evaporated, reused and/or disconnected from the sewer system. This is exactly what cities such as Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, PA are trying to accomplish.