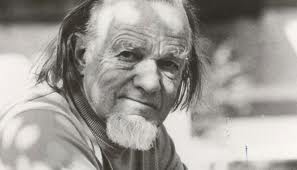

Growing up in an Evangelical Christian home, my disappointment in how my form of  Christianity thought about and responded to environmental problems was inescapable. Biblical teaching regarding dominance over nature was misconstrued and took precedence over reverence and respect. But there was one prominent voice within the evangelical movement who strongly disagreed. In 1970, Dr. Francis Schaeffer, an evangelical theologian and philosopher, penned the book, “Pollution and the Death of Man: the Christian view of ecology,” which is still available in reprinted version. It’s a short read, little more than a hundred pages and a couple of hours of reading. The other night I blew the dust off my original, dog-eared, margin-smudged version that I kept near my night-stand during my youth as I struggled with faith and fauna. Its content and message of why Christian stewardship of the environment matters are still very relevant today. Schaeffer wrote the book during a time of environmental awakening in the U.S., shortly after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring but before the advent of federal environmental laws, such as the Clean Air and Water Acts.

Christianity thought about and responded to environmental problems was inescapable. Biblical teaching regarding dominance over nature was misconstrued and took precedence over reverence and respect. But there was one prominent voice within the evangelical movement who strongly disagreed. In 1970, Dr. Francis Schaeffer, an evangelical theologian and philosopher, penned the book, “Pollution and the Death of Man: the Christian view of ecology,” which is still available in reprinted version. It’s a short read, little more than a hundred pages and a couple of hours of reading. The other night I blew the dust off my original, dog-eared, margin-smudged version that I kept near my night-stand during my youth as I struggled with faith and fauna. Its content and message of why Christian stewardship of the environment matters are still very relevant today. Schaeffer wrote the book during a time of environmental awakening in the U.S., shortly after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring but before the advent of federal environmental laws, such as the Clean Air and Water Acts.

As society’s collective awareness of ecology began to grow during that time, especially in light of concerns regarding the destructive forces of modernity, there was an attempt by some to explain how we in Western society had allowed our environment to be degraded to the point it had. The environmental movement was largely a product of the 1960s counterculture and hippie youth movement, and their belief in humanism and pantheism, not those professing Christianity, and the driving force behind this awakening. Some intellectuals, including Lynn White, Jr., a Princeton Professor of medieval history, who wrote a piece titled, “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis,” laid blame squarely on exploitive views of certain kinds of Christianity. According to White,

exploitive views of certain kinds of Christianity. According to White,

Christianity, in absolute contrast to ancient paganism and Asia’s religions (except, perhaps, Zoroastsrianism), not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends.

At the level of the common people this worked out in an interesting way. In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns, and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated. By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.

The discussion continued on the proper solution to the problem, and some intellectuals embraced pantheism, the belief that God is present in everything, including objects of the natural world, such as trees, flowers, birds, streams and rocks. Schaeffer, accepting criticism of certain kinds of Christianity as creating an indifference toward environmental stewardship, argued for a different kind of or understanding of Christian faith.

It is well to stress, then, that Christianity does not automatically have an answer; it has to be the right kind of Christianity. Any Christianity that rests upon a dichotomy – some sort of platonic concept – simply does not have an answer to nature, and we must say with tears that much orthodoxy, much evangelical Christianity, rooted in a platonic concept, wherein the only interest is the “upper story,” in the heavenly things – only in “saving the soul” and getting it to heaven. In this platonic concept, even though orthodox and evangelical terminology is used, there is little or no interest in the proper pleasures of the body or the proper uses of the intellect. In such a Christianity there is a strong tendency to see nothing in nature beyond its use as one of the classic proofs of God’s existence. “Look at nature,” we are told; “Look at the Alps. God must have made them.” And that is the end. Nature has become merely an academic proof of the existence of the Creator, with little value in itself. Christians of this outlook do not show an interest in nature itself. They use it simply as an apologetic weapon, rather than thinking or talking about the real value of nature.

Schaeffer believed that nature was important, more than just for purely pragmatic human reasons, and should be respected because God made it. This was sufficient grounds. It wasn’t because, according to pantheistic belief, the value of a thing such as a tree or stream was somehow autonomous or have some sort of divine existence in itself; rather a Christian attitude of care must flow from a respect and integrity for something which God, through the sphere of creating, saw as good and fit for human entrustment. It’s a simple construct, but one that alarmingly seems foreign to so many Christians. According to Schaeffer, “Christians, of all people, should not be the destroyers. We should treat nature with an overwhelming respect” and “each thing in its own order, each thing the way He made it . . . the tree like a tree, the machine like a machine, the man like a man . . .” This to me seems to be the correct Christian approach.

Much scholarship on Christian attitudes toward environmental stewardship has been authored since 1970, but Schaeffer’s book is still very relevant and worth the read.